“You’re the first tourist to ever see this,” Tatjana whispers as she kills the engine on the ATV. The silence is so complete across the vast open steppe that I suddenly feel as if I’ve been struck deaf. In the distance, six dark burnt-orange shapes huddle on the featureless grassy horizon. Then a soothing singsong voice fills the air in plaintive lilting Russian.

“Aye, Zolotie zaichiki … (my little golden hares) … Aye, Serebryanie kurochki … (my little silver hens)”

Massive heads rise in the distance with perked ears pointing toward us like satellite dishes.

“Krasavchiki … (my prettiest creatures) … Devochki malchiki moi … (my sweet girls and boys)”

Their defensive postures change to delight and excitement and they move rapidly toward us, heads bouncing up and down with eager looks of anticipation. Even across species, it is obvious what they are thinking: It’s you! We’re so glad you’re here!

“Kotyatki moi … (my little kittens) … Ushastiki … (my fluffiest little ears)”

My heart begins to pound as the creatures grow larger, hooves clomping toward us in the soft soil. There’s no denying it now. The critically endangered Przewalski’s Horse has officially returned to the Russian steppe.

She speaks in low tones as she climbs off the ATV. “Stay on the bike and move slowly and quietly. They know me and my voice but they may be afraid of you.”

She unties a small sack of oats from the front of the quad and spreads them into little piles on the ground.

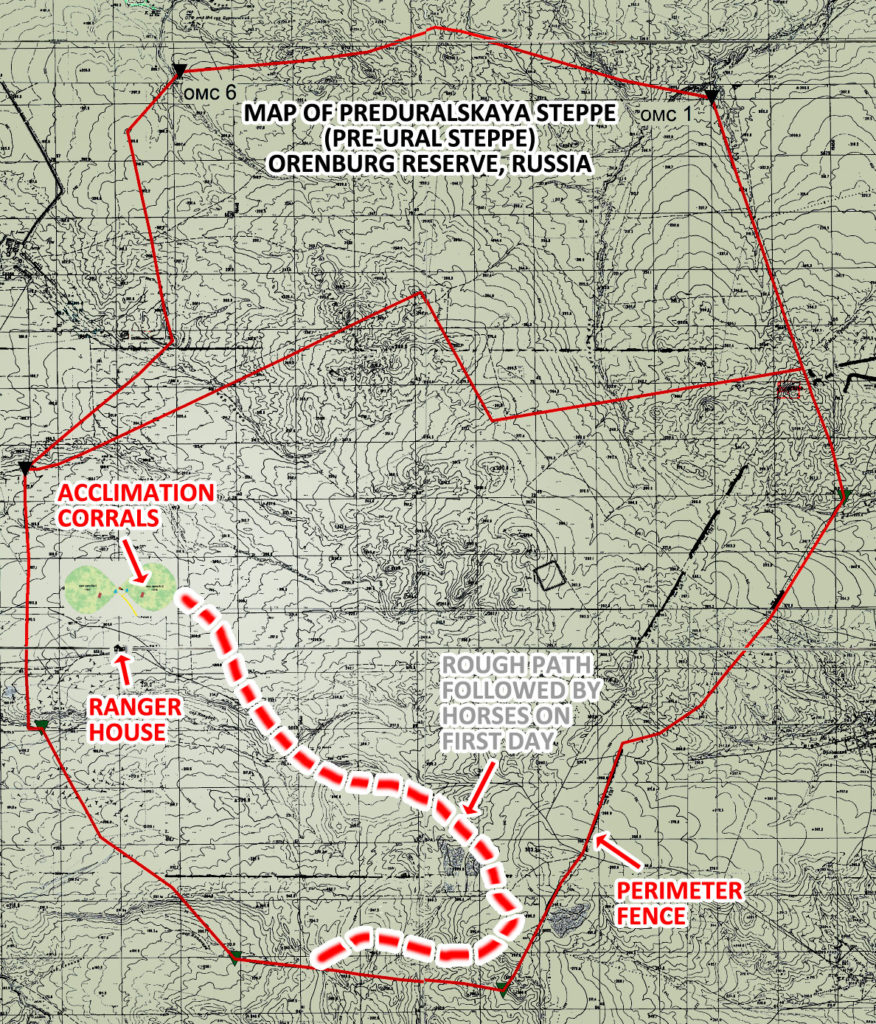

“Aye, Selena, Aye, Lavanda, Aye aye aye…” She calls to them by name as one by one they stride toward her and cautiously acknowledge her. After spending a full year in the acclimation corral, they are now out here all alone in a strange new place for the first time, with 40,000 acres of unknown territory to navigate. Their new home is the Preduralskaya Steppe (which in English translates as the Pre-Ural Steppe) in Russia’s Orenburg Reserve. It is only their second day in the wild.

As the head of this reintroduction project, Tatjana Zharkikh is a familiar and welcome face. “Aye, Sangria … Aye, Olive…” she sings.

I am a stir of emotions. The honor and responsibility of being the first person to witness this historic event, in the lone presence of a woman that I admire so greatly, is humbling and overwhelming. The thrill of being so close to a large wild animal courses through me, but it is immediately tempered by the sobering reality that they and their kind still hover on the brink of extinction. Above all, the tender sweetness of this intimate moment brings a teary-eyed lump to my throat.

The gentle breeze carries smells of tarragon and sage while the horses munch loudly on their treats. All six of them mill about directly in front of me. Lavender, the youngest mare, walks right up to the front of the quad bike, just three feet away from me, and sniffs the spot where the oats were tied, eyeing me curiously.

The feisty blonde mare named Olive earns her reputation as a trouble-maker and nips Lavender on the rear.

To my left, Selena and her son Paprika cuddle close together and nudge each other softly.

To my right, Tatjana stands at a short distance, photographing the horses and explaining who is doing what. “Sangria is a beautiful horse,” she coos lovingly, more to the horse than to me.

Behind them all, Aven stands with solid confidence. He is the stallion, the benevolent patriarch of this small band of six survivors. Aven is recognizable by his stout masculine features, dark coloring, and the deeply-scalloped white heart-shape that surrounds his muzzle.

The vision of these grazing horses looks familiar on the surface, but the feelings they evoke inside are something entirely new to me. For the first time in my life, I’m looking upon a horse as a wild animal. For the Przewalski’s Horse is the only true wild horse left on the planet. Every horse I’ve ever seen in my entire life up to this point has been a domesticated horse.

******

A Brief History of the Przewalski’s Horse

I know the name Przewalski is a daunting obstacle to overcome. Americans like me pronounce it shuh-VAHL-skee. Some call it a P-horse. The name comes from the great Russian explorer, Nikolay Przhevalsky who brought back the remains of a wild horse from Mongolia in the late 1800’s. Others call it the Mongolian Wild Horse because that’s where the last remaining wild population persisted. I prefer the name Asian Wild Horse because just a few hundred years ago this majestic animal ranged all across the Asian steppes, from Russia and Kazakhstan in the east, to Mongolia and northern China in the west.

Then the population went into a free-fall. There were a variety of contributing factors, including hunting, competition with livestock, and possibly climatic change. The last wild sighting occurred in the 1960’s. Then the species was officially declared extinct in the wild.

However, several expeditions in the early 1900’s captured wild individuals and transported them to European zoos. Undoubtedly these roundups also contributed to the rapid decline of the species in the wild. All Przewalski’s Horses alive today are descended from just 12 of these wild-caught animals.

Thanks to an impressive international conservation effort, there are approximately 2000 alive today. A small number live in zoos across the world, while the rest are spread between a handful of large enclosed reserves and wild reintroduction sites in Mongolia, China, Kazakhstan, Uzbekistan, Ukraine, Hungary, and France.

And now, thanks to a partnership with the UNDP/GEF, the largest country on Earth has joined the effort and is bringing the Mongolian Wild Horse back to the Russian Steppe. (UNDP/GEF stands for the United Nations Development Program/Global Environment Facility)

******

Drama on the Steppe: Social Dynamics of the Przewalski’s Horse

Tatjana explains some of the group dynamics to me as the horses pace slowly back and forth. Although they seem to be constantly on the move, they maintain a tight grouping, just as their social relationships are constantly shifting but the unity of the herd never falters.

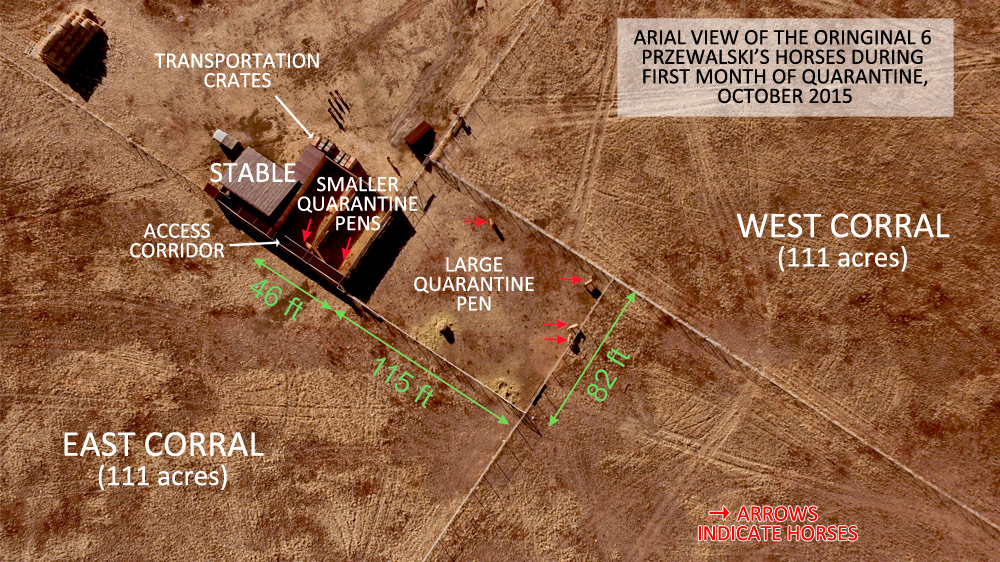

One year ago, all six of these horses were transported from Le Villaret semi-reserve in France, managed by an organization called TAKH (Association pour le Cheval de Przewalski). Upon arrival, Selena and her one-year-old son Paprika were kept in the smaller, high-walled pens during the first month of quarantine.

Aven (the stallion) and the three mares Sangria, Olive, and Lavender were kept in the other, larger fenced corral next door where they could hear and smell each other.

After the month of quarantine was up and everyone was deemed healthy, Selena and Paprika were the first to be released into one of the two 111-acre acclimation corrals. Then, after some debate as to how to proceed, Aven was released into the same corral.

At first Aven was aggressive toward the new members of his harem. “He attacked Selena and Paprika immediately.” The young colt Paprika received the brunt of the assault, until he quickly learned to submit to the dominant stallion. Tatjana tells me that Aven then treated Selena and her colt “more or less tolerably.”

When I asked reserve staff yesterday about how the relationships evolved, my interpreter Anastasia Lukinskaya relayed the question in Russian. Broad grins crossed their faces. “Aven ‘fell in love’ with Selena,” Anastasia translated back with a bashful smile and blushing cheeks. “The other mares were extremely jealous and we could hear them screaming from their holding pen.”

When the three mares were released into the same corral, things got even more complicated.

The females maintain their own social hierarchy within the herd but, as the top male, Aven gets to choose where his affections will lie. At eight years old, Selena is the highest ranking among the females. Sangria holds second rank. Olive, the third-ranking female seems to spend the most time in close proximity to Aven (is she trying to make a move?)

But Aven is most tolerant of the youngest mare, Lavender. Although she is the lowest-ranking female, she appears to be Aven’s favorite lady.

Meanwhile Paprika, now two years old, grows up in Aven’s shadow with secret dreams of becoming top stallion himself one day. Or at least stealing some romantic moments with the other mares. “Paprika takes any chance he can to prove he’s a man too,” I’m told with a wink. “Selena and Sangria are still enemies to this day,” they confide. It’s hard to imagine a soap opera with a juicier plot.

Lavender is full of confidence and curiosity as she strides toward me again, then back to Aven’s side. Now Selena and Paprika are heading away and Sangria follows. As quickly as it began, the horses begin to disperse in a loose line toward the rising sun on the southeast horizon. Olive joins the march.

“Aven is always the last to leave,” Tatjana explains. “But if he isn’t ready to go, the rest of the group will turn around and come back.” Lavender finishes her oats and joins the formation. Aven glances after them from time to time but continues munching. Finally, as the group crests a hill, Aven turns to go and plods slowly after them. His movements are deliberate and solid. His gait conveys a self-assured swagger, like a cowboy entering a saloon.

His massive muscular neck, short powerful legs and convex forehead are the hallmarks of a true wild horse. Even the tail is easily distinguished from a domestic horse. Short bristly guard hairs cover the base of the tail as if a hedgehog were clinging there, and a thin dark line runs up the spine. But the real dead giveaway of any domestic horse is the mane.

******

Domestic Horses vs. Wild Horses

All seven of the remaining wild equid species (members of the horse family) have short, erect, brushy manes. This includes the zebras (Mountain, Grevy’s, and Plains), the wild asses (Kiang, Onager, and the African Wild Ass) and the Przewalski’s Horse.

The long luxurious mane that we are used to seeing on horses today is a product of human domestication.

What about the Mustangs in the American west or the Brumby in Australia? We are used to calling them wild horses, but both are colonies of feral domesticated horses which were brought to each continent a few hundred years earlier by Europeans.

So who is the ancestor of all these domestic horses? Like most taxonomic questions, experts disagree, but here is the general story.

The original wild horse used to exist in a continuous band from Europe all the way to Mongolia. The wild horses at the western (European) end were referred to as the Tarpan (or the Eurasian Wild Horse) while the horses at the eastern (Asian) end are referred to as the Przewalski’s Horse (or Mongolian Wild Horse). Whether these horses constituted separate species or were subspecies of the same animal is up for debate. But what we do know, thanks to genetic research, is that all the domestic horses alive today are not descended from the Przewalski’s Horse. They are all descended from either the Tarpan, which went extinct in the 1800’s, or perhaps a similar as-yet undiscovered species which went extinct in the wild even earlier. Yet their domesticated descendants flourished and were spread across the world by humans.

Domestication of the wild horse began as long as 5,000 years ago by the Botai people of what is now northern Kazakhstan, very close to where I am now standing in Orenburg, Russia. At first, horses were raised for food but their eventual use as transportation quickly elevated their status above all other domesticated creatures, perhaps even reaching a level as high as man’s best friend: the dog. Over time, and under the selection of human breeders, domestic horses got taller, their legs got longer, and their features thinned out while the mane grew long and luxurious.

This leaves the Przewalski’s Horse as the only true wild horse on the planet, never to have been domesticated by humans.

Although the lineage leading to today’s domestic horses diverged from the Przewalski’s horse lineage more than 45,000 years ago (some studies say as many as 250,000 years ago), they remain closely related. Despite possessing a different number of chromosomes (66 in the Przewalski’s, 64 in the domestic), they are still able to interbreed and produce fertile offspring. This close relation is ironically one of the biggest threats to their recovery as a species.

******

The Longest Fence in Russia

Tatjana tells me we can now follow the group on foot so I slide off the ATV and grab my camera gear. It has been a dry summer and the short yellow-brown herbs rustle under our feet. The yellowish feather grasses and the green fescues are the primary food source for the horses, but they will eat a wide variety of plants on the steppe.

What is Steppe? Basically it’s another word for grasslands. The North American equivalent would be the Prairies. It’s an ecological zone that is too dry to support trees (except next to rivers and lakes) but too wet to be considered a desert. This is where the grasses thrive and the Przewalski’s Horse is perfectly adapted to it.

The small herd stops to graze and we approach them at acute angles to give the appearance that we’re just going about our own business. Fresh air, cool sunshine, and a feeling of peace wash over me as we watch the herd. They ignore us as if we were just another herbivore out here on the steppe. Then their attention is drawn to a strange shape on the horizon. It is a large wagon, hitched to the back of a tractor.

The horses hold their heads high, ears perked forward. Their inquisitive nature draws them inexorably forward. With hesitant steps they move toward the unknown object. This irresistible curiosity is a trademark of the Przewalski’s horse, and probably served them well in the many thousands of years of adaptation to the vast Asian steppe environment. But it also made them easier to hunt when humans came along with long-range weapons, and it was surely a contributing factor to their near-extinction.

Soon the herd has satisfied its curiosity and walks on. The six-foot-high perimeter fence is visible in the distance. Tatjana shakes her head and stares pensively for a moment. “When some Russian scientists first came out here several years ago to discuss the possibility of a reintroduction project, they urged us not to erect a fence. But now I’m very glad we did.”

Many assumed the horses would stick around the acclimation corrals after their release two days earlier. But instead they immediately struck out for the horizon. When I first met Tatjana upon my arrival yesterday she looked exhausted and anxious. Nobody had any idea where the horses had gone overnight. Tatjana was extremely worried about her babies. With 64 square miles of ground to cover and no tracking devices, it was anybody’s guess. Thankfully she managed to locate them for the first time yesterday afternoon near the central southern end of the reserve. They had wandered straight toward the southern fence line.

This morning, when she and I headed out alone on the ATV to find them again, we still had no idea where they might be. We stopped on hill tops and scanned in every direction, constantly watching the horizon for a cluster of dark shapes. After an hour of driving and fruitless searching we stood atop a high hill and gazed with quiet intensity, Tatjana through her monocular to the east and I through my binoculars to the west.

“I see something,” she said calmly, belying the immense relief she must have felt inside. They were still in the south end of the reserve, close to the fence. Without the fence, who knows where they might have wound up by now. Odds are, they would find themselves in the field of a nearby village, surrounded by domestic horses.

“No horse is safe from Aven’s affections,” a staff member joked to me yesterday. But interbreeding with domestic horses is one of the greatest threats to the resurrection of the species. Within just a few short generations, the offspring of the hybrids would hardly resemble the wild Mongolian horse they had once been. If allowed to freely interbreed, the Przewalski Horse gene pool would essentially be absorbed into the huge domestic horse population and the wild horse would truly become extinct.

The thin galvanized wire glimmers in the sunlight. Long streamers of parachuting spider webs stick to the top and wave like jellyfish tentacles in the breeze. I’m told it is the longest fence in Russia, and at 32 miles in length, it certainly is a monumental achievement. It surrounds an area of virgin steppe as big as the entire country of Liechtenstein. And though it may seem a contradiction to call these horses wild when their kingdom has a border around it, without the fence there might be no wild horses at all in Orenburg.

Some parts of the world are so sparsely populated that reintroductions have been attempted without a protective fence, such as in the Gobi Desert, and the Chernobyl Exclusion Zone in the Ukraine where Tatjana worked before this project. But each one has its own unique set of challenges to face, from extremely harsh winters, to hunting by poachers.

The small herd of horses plods on toward the fence. Though they appear to be moving in slow motion, they quickly outpace us. Tatjana turns to me and says, “we’ll let them be for now.” She turns her back to them and looks into the distance over my shoulder with a small sigh and a smile upon her face. “I feel happy and calm.”

******

The Future of the Przewalski’s Horse in Russia

Next month, in November of 2016, fifteen more horses will be arriving from a reserve in Hungary. They will go through the same acclimatization period as the first six horses, spending a month in the quarantine pens, then roughly a year in the corrals. When they are deemed ready, they too will be released into the reserve. Then things will really start to get interesting.

The goal is to have 150 horses living in the reserve by 2030, consisting of more stock transferred from other reserves as well as any foals born from the resident herds. By some estimates, this reserve could sustain a population as large as a thousand one day.

Tatjana also hopes to eventually reintroduce other large grazers such as bison into the reserve, to help keep the ecosystem healthy. The plants in the steppe co-evolved with a suite of large grazers, and together they formed a sort of co-dependent relationship. Each has learned to survive and thrive in the presence of the other. Perhaps one day even predators, the final piece of the puzzle, will be allowed to return and the ecosystem will be whole again.

******

How to see the Wild Przewalski Horses in Russia: Ecotourism in Orenburg Reserves

I was indeed the first tourist to witness the spectacle of a wild Przewalski’s Horse in Russia. But soon, others will be able to follow in my footsteps.

Infrastructure is already being built to accommodate visitors. The small compound currently boasts a beautifully constructed ranger house where I spent the night. The room I slept in had a wall of windows with panoramic views across the steppe toward the corrals. And of course, the ranger house has its own banya (Russian sauna). There are plans to build a visitor center and guest accommodations within the next two years. Outside, the view of the night sky was unlike any I had ever seen. The Milky Way split the sky perfectly in half while red sparks flew from the chimney top above the banya wood stove.

The ranger house is powered by a large solar panel, as well as a nearby generator bunker. There are two picnic shelters with outdoor fireplaces, a lovely wood-planked restroom, and a banner display wrapped around a yurt.

Tidy concrete paver paths connect all the structures. An educational eco-trail leads from the compound to the acclimation corrals and is lined with 10 beautifully-designed informative displays.

On my first day at Pre-Ural Steppe, the reserve Director herself, Rafilia Bakirova, along with Vice-Director Andrei Latypov and Press Secretary Natalia Sudets gave me a personal guided tour of the eco-trail and the horse facilities. And of course my trusty translator Anastasia helped me to understand everything that was going on.

In front of the corrals are two of the actual crates used to transport the six horses from France a year earlier. Each was custom-designed to fit an individual horse. One has the word AVEN scrawled onto its side with black marker and the other is marked PAPRIKA. As I stooped inside Aven’s crate, I realized that the Przewalski’s Horse is indeed substantially shorter than the modern domesticated horse.

Behind the crates we encounter the stables, designed to care for horses that fall ill, which have thankfully never been used. Next to the stable are the two smaller quarantine pens surrounded by tall wood-planked walls. Behind both is a high-fenced corridor used to move horses safely from one enclosure to another and to administer medications if necessary. To either side, the immense acclimation corrals spread into the distance. From above it looks like a huge figure-8. Each of the two circular corrals encloses about 111 acres of virgin steppe and meet at the quarantine pens in the middle. They tell me these are the only round corrals of this magnitude in the world. They were built round because 1) it allows horses to run in a continuous circle without hitting corners, and 2) because it is the most efficient use of fencing to enclose the maximum area possible.

I stood in front of the eastern corral where the horses had spent the last eleven months, and realized that just 24 hours earlier, the president of the Russian Federation, Vladimir Putin, was standing in this very spot releasing the horses into the wild. I even sat upon the same ATV that Putin rode, Tatjana’s personal blue ATV that the horses are accustomed to. Yes, I put my butt in the same place where Vladimir Putin had put his just one day earlier. That’s something I never expected I’d be able to say.

When I asked Tatjana about the prospects of bringing tourists to the reserve, she said she hoped that this would be possible within the coming year. For the next few months they’ll be very busy with the new batch of horses arriving from Hungary, but after that they hope to be able to focus more attention on their ecotourism objectives.

Until that day, you can check out the Dersu Uzala website (view in google chrome and turn on translation) or the Dersu Uzala Ecotourism Project website to learn more about the new wave of ecotourism opportunities being developed in Russia. For more information on ecotourism in Russia, you can send an email to ecotrails.russia@gmail.com. If you’d like to learn more about the Orenburg State Reserves, including Pre-Ural (Preduralskaya) Steppe, you can visit the Orenburg Reserve website. (Again, you’ll have to turn on translation in google chrome.)

Soon, people from around the world will be able to experience the thrill of seeing the wild horse returned to its ancestral home on the Russian steppe.

I’d like to give a special thanks to the Dersu Uzala Ecotourism Fund, and the US-Russia Peer-to-Peer Dialogue Program funded by the US Department of State, for making my trip to Russia possible, and especially Elena Bazhenova for all her hard work organizing my visit. Stay tuned for an upcoming photo essay of my week of adventures in the Orenburg Reserves!

Disclaimer: This article was funded by a grant from the United States Department of State. The opinions, findings and conclusions stated herein are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect those of the United States Department of State

If you enjoyed this post, Pin it!

Hal Brindley

Brindley is an American conservation biologist, wildlife photographer, filmmaker, writer, and illustrator living in Asheville, NC. He studied black-footed cats in Namibia for his master’s research, has traveled to all seven continents, and loves native plant gardening. See more of his work at Travel for Wildlife, Truly Wild, Our Wild Yard, & Naturalist Studio.

Camille

Wednesday 4th of October 2017

Very lovely article, my sister work as a volunteer with those horses in France and they are very dear to her. Thank you for the report on their health (though, it's been a while now, things might have changed, if you've had any news since, could you update us?). Merci :)

Alexander

Monday 24th of October 2016

Great job! Orenburg is my home city. Now I want to visit the Reserve you told us about so eloquently)

Hal Brindley

Monday 24th of October 2016

Thanks Alexander! The reserve is closed to the public at the moment but I think it may be possible to apply for a visitor's permit through the Orenburg Reserves website listed at the end of my article. I really enjoyed your town and especially the people I met there. Thanks for checking out the site! -Hal